The Nature of Monsters

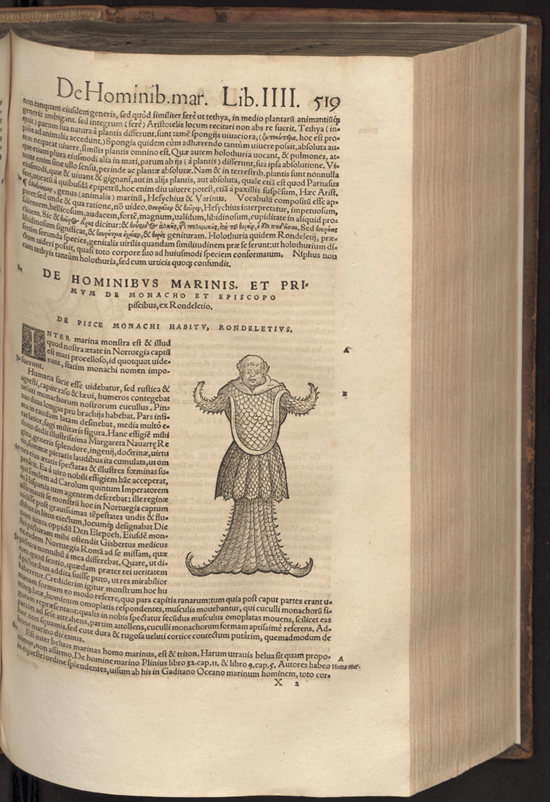

In Antiquity nature in general was seen as flexible and capable of producing any variety of creatures. This was believed to be particularly true for aquatic environments. The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder stated that monstrosities form most easily in water, due to its liquid nature and the amount of nutrients it contains. Later on, Christian authors presented this plasticity of nature as the consequence of divine omnipotence. As a result, monsters were on the one hand seen as natural phenomena and on the other often interpreted as divine signs. For example, several sixteenth century scholars describe a ‘sea-monk’, a creature with a tonsured head and scaly robes. This was interpreted by the religious author and counter-reformer Aegidius Albertinus (1560–1620) as a divine expression of dissatisfaction with the hypocrisy of the clergy, while the scholar Paracelsus (1493–1541) provided a natural explanation for its existence by stating the creature must be the offspring of a fish and a drowned monk.

Monachus marinus, in Conrad Gessner, Historiae animalium liber IIII qui est de piscium et aquatilium animantium natura, Zürich, C. Froschauer, 1558, p. 519. [Leiden University Library, 665 A 7]

Terrestrial Counterparts

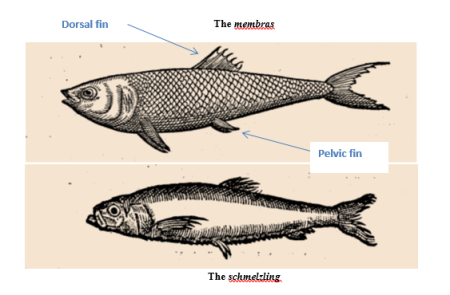

Like the sea-monk, many aquatic monsters resembled something or someone we might find on land. Since Antiquity it had been assumed that aquatic creatures often took the form of a, natural or artificial, terrestrial counterpart. As evidence of this principle, classical authors referred to creatures such as the sea-cucumber, the swordfish, and the sawfish. Classical mythology also featured a range of aquatic deities with human upper bodies and the lower body of a fish, such as Nereids, as well as creatures which were part terrestrial animal, such as the hippocampus, with the upper body of a horse and lower body of a fish. Descriptions and depictions of sea-monsters from the Middle Ages and the Early Modern era show us similar mixtures of aquatic and terrestrial features. The popular late fifteenth century natural history encyclopedia Hortus Sanitatis for example, presents to us a range of sea-creatures with terrestrial characteristics. The illustration shows a page from a 1536 German edition, Gart der Gesundheit, which bears depictions of a sea-cow with the upper body of a cow and lower body of a fish, a bird with a fishtail, and several Nereids.

Various monsters and mythical creatures, in Gart der Gesundheit zu latein Hortus Sanitatis : Sagt in vier Bücheren von Vierfüszsigen vnd Krichenden, Vöglen vnd den Fliegenden, Vischen vnd Schwimmenden thieren, dem Edlen Gesteyn vnd allem so in den Aderen der erden wachsen ist, Strasbourg, M. Apiarius, 1536, fo. XCII. [Leiden University Library, 1370 B 15]

Mermaids

While there was much continuity in the way sea-monsters were portrayed and perceived, new developments also took place. While mermaids were unknown in Antiquity, sightings of these creatures were reported with some regularity by Medieval and Early Modern authors. A page-wide depiction in a work on monstrosities, Monstrorum historia (1642) by the first professor of natural sciences at the University of Bologna and founder of its botanical garden, Ulysse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), shows us what such creatures were believed to look like. In appearance these much resemble the Nereids from Antiquity, which were believed to be friendly and keen to help sailors in distress. In this, they resemble the benevolent aquatic fairies native to western European folklore. By contrast, mermaids were believed to be dangerous and seductive creatures that shipwreck vessels and lead sailors to their doom. In this, they resemble another creature from classical mythology, the siren. These birdlike creatures with human faces were believed to enchant sailors with their singing in order to cause them harm. During the Middle Ages, elements of sirens, sea nymphs, and aquatic fairies, were combined in popular imagination to form the mermaid.

Monstra Niliaca, in Ulisse Aldrovandi, Opera omnia. XI Monstrorum historia cum paralipomenis historiae omnium animalium, Bologna, N. Tebaldini, 1642, p. 354. [Leiden University Library, 655 A 13]

Monstrous Whales

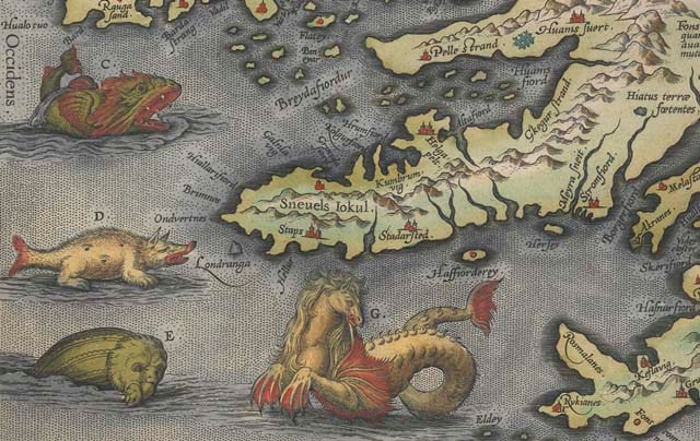

While monstrous whales had been described since Antiquity, the sixteenth century generated an unprecedented variety of such creatures. Little knowledge on whales had been gathered during Antiquity and the Middle Ages, and often monstrous proportions and strength were attributed to these animals. For unknown reasons, in the second half of the sixteenth century whales beached more frequently than usual on European shores. Around the same time whaling increased. As a result, knowledge expanded, but up until then accurate depictions and descriptions were scarce and the line between whale and monster remained difficult to draw. The Swedish chronicler Olaus Magnus published depictions of monstrous whales based on folklore on his 1539 map of Scandinavia Carta marina et descriptio septentrionalium terrarium and in his 1555 chronic of Scandinavia Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus, which became instantly popular. The creatures shown on the map of Iceland from the Antwerp cartographer Abraham Ortelius’s atlas Theatrum orbis terrarum (1570) are based on Magnus’s monsters. The map shows ten monstrous whales, with claws that resemble those of terrestrial animals.

Islandia, in Abraham Ortelius, Theatrum orbis terrarum, Antwerp, s.n., 1570. [Leiden University Library, COLLBN Atlas 43: 1]

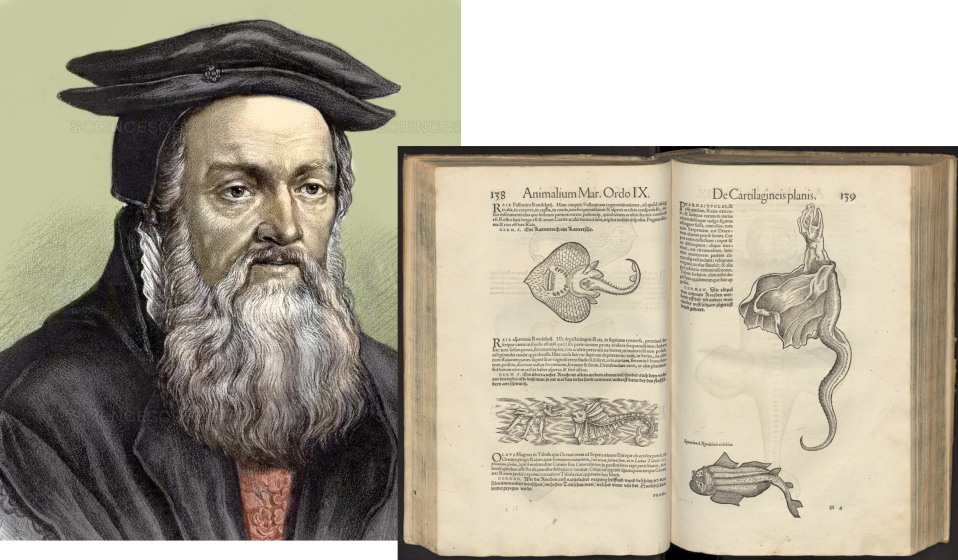

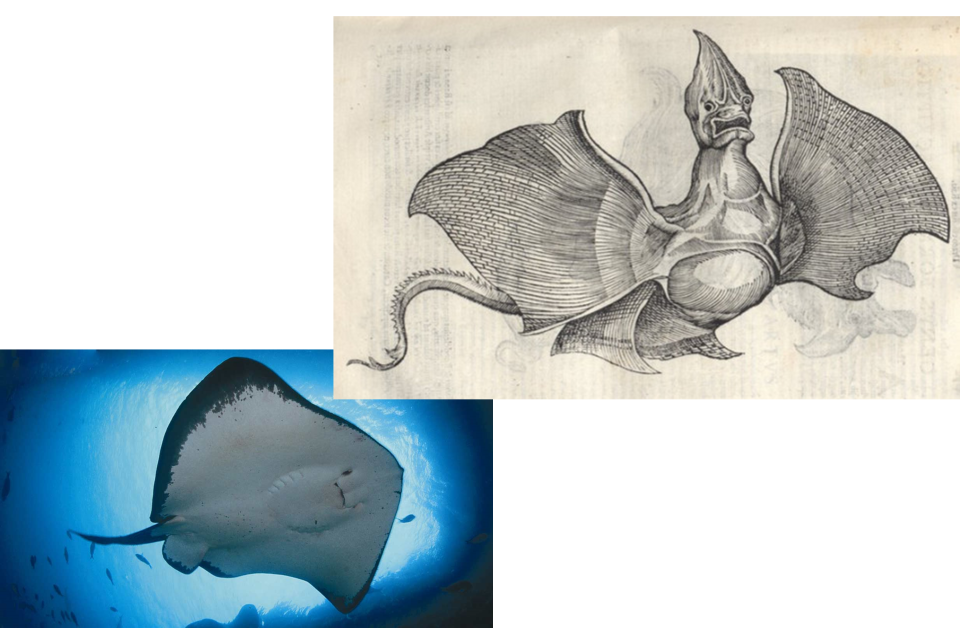

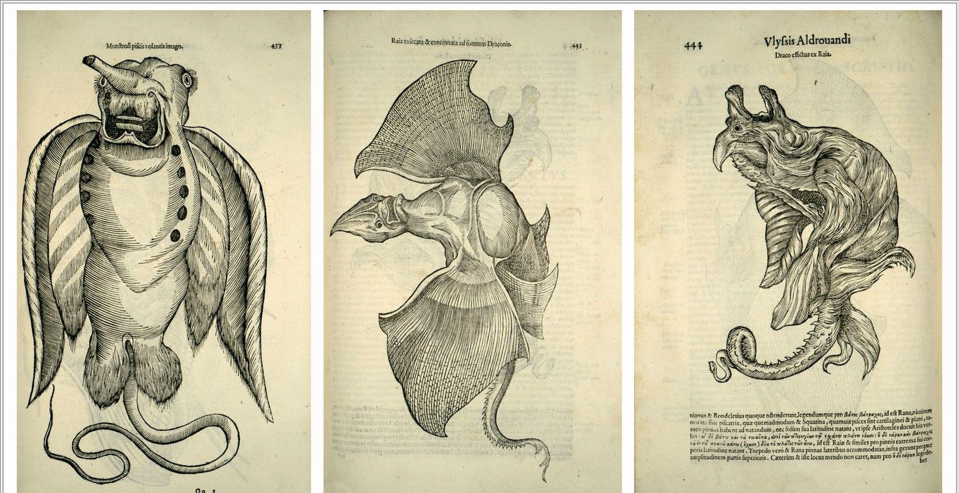

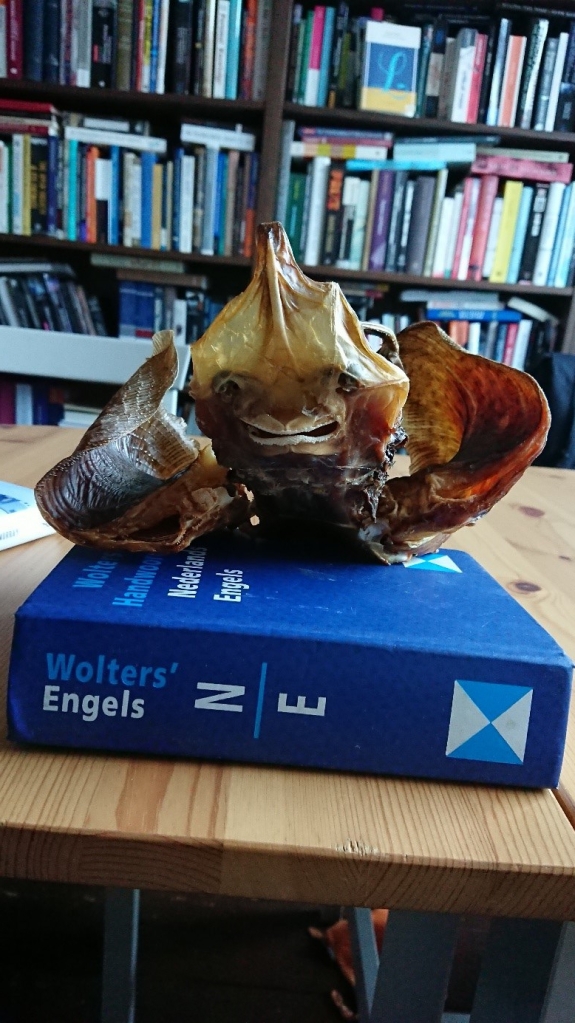

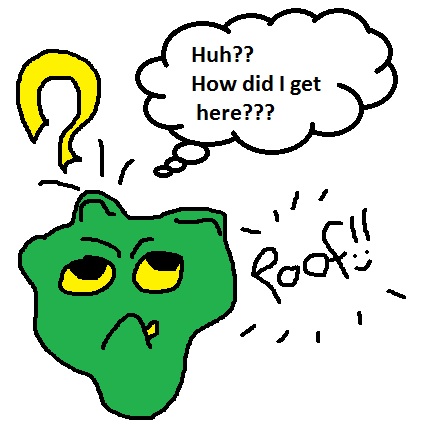

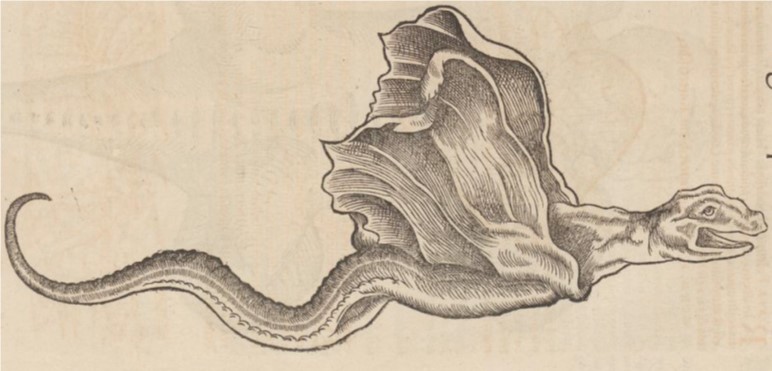

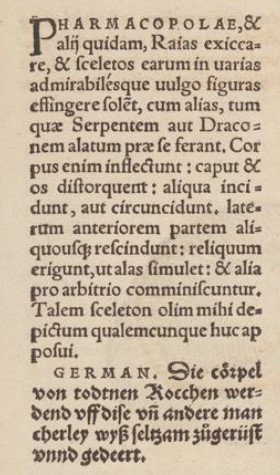

Man-Made Monsters

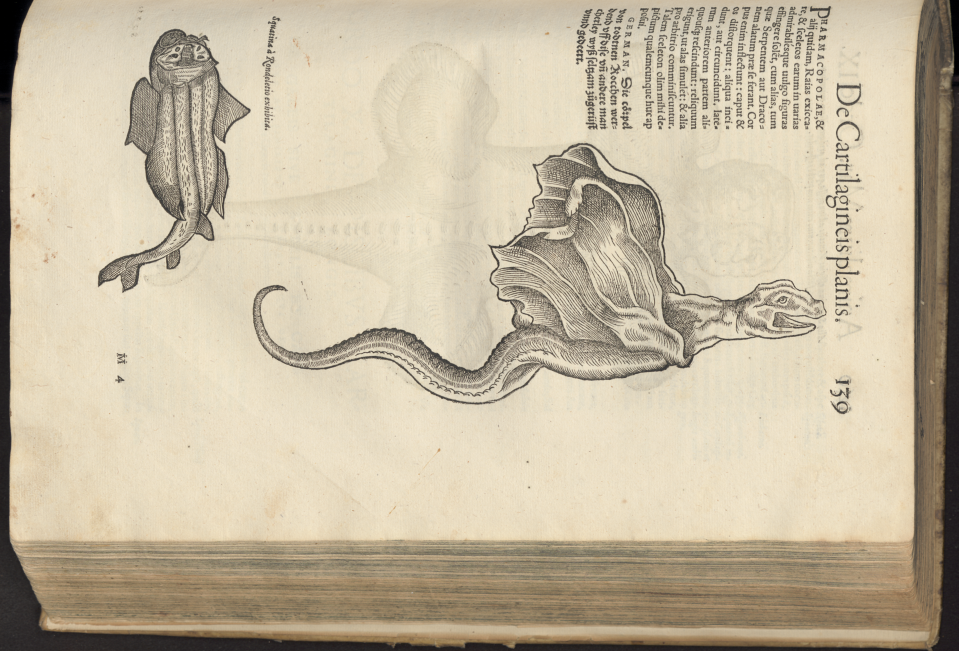

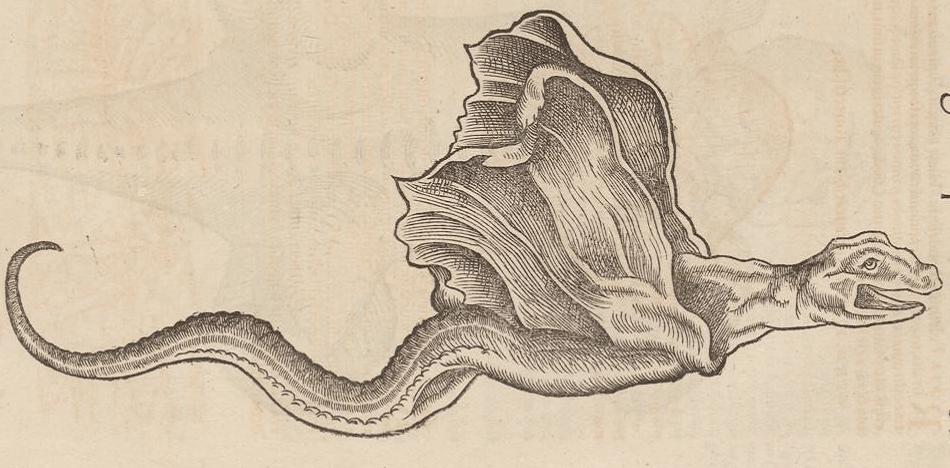

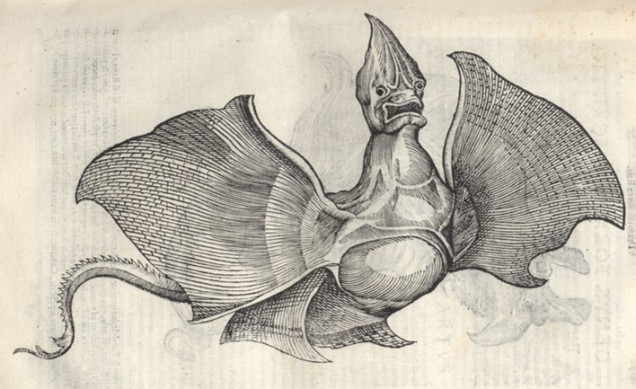

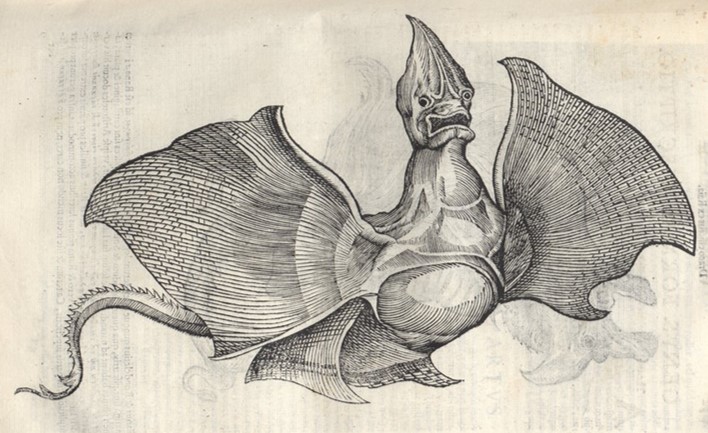

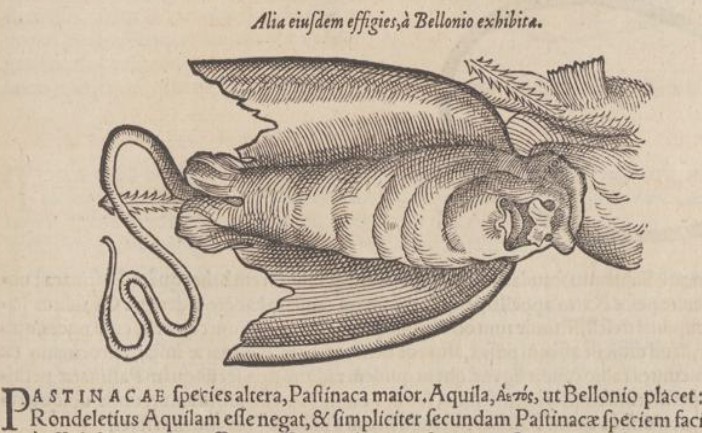

Basilisks were first described in Antiquity as dangerous serpents and acquired new characteristics in later centuries. By the late Middle Ages they had become winged monsters, born as the result of a bizarre sequence of events, which could kill anyone by looking at them. During the Early Modern period basilisk-like monsters were manufactured out of rays. The scholar Ulysse Aldrovandi describes two such creations as basilisks, while others are described as winged snakes or dragons. In 1558 the Swiss scholar Conrad Gessner (1516–1565) explained, in his encyclopaedia of animals Historia animalium, how these were made, by twisting, cutting and drying a ray. He complains that the man-made monsters were passed off as real to impress the masses and were often exhibited in apothecary shops. However, they were also part of scholarly naturalia collections. Aldrovandi collected several and described no fewer than five in his Serpentum et draconum historiae (1640) and De piscibus et de cetis (1623).

Winged snake, in Conrad Gessner, Nomenclator aquatilium animantium icones animalium aquitilium in mari et dulcibus aquis degentium, Zürich, C. Froschauer, 1560, p. 139. [Leiden University Library, 665 A 9]

Draco ex Raia effictus, in Ulysse Aldrovandi, Opera omnia. X: Serpentum et draconum historiae libri duo, Bologna, N. Tebaldini 1640, p. 315. [Leiden University Library, 655 A 12]

The Sea-Unicorn and the Narwhal

First reports of the unicorn date back to the fourth century BC, when the scholar Ctesias described a one-horned horse which he had heard about. The legend subsequently spread through the work of Aristotle and other scholars. In addition, a mistranslation in the bible gave the impression that the unicorn was mentioned in the Old Testament. Scholars of the Middle Ages and first half of the Early Modern period consequently had good reason to believe in unicorns. The assumption that animals on land have aquatic counterparts, meant that the existence of a sea-unicorn was also widely accepted. Believed to neutralise poison, what was sold as unicorn horn fetched exorbitant prices. In the sixteenth century scholars began to suspect that these ‘horns’ were in fact narwhal teeth. The collector Ole Worm published a treaty on this subject in 1638. The discovery quickly became common knowledge and inspired the depiction from Pierre Pomet’s Histoire generale des drogues, published in 1694, of a sea-unicorn and narwhal side by side. However, rather than diminishing belief in the medical properties of the horns, this led many to belief that the narwhal was in fact the sea-unicorn. The last recorded use of unicorn horn in folk medicine took place in the nineteenth century.

Licorne de Mer, in Pierre Pomet, Histoire generale des drogues, traitant des plantes, des animaux, et des mineraux, Paris, J.-B. Loyson, etc.,1694, p. 78. [Museum Boerhaave Library, BOERH e 2459 a]

Modern Sea-Monsters

Certain sea-monsters have proved surprisingly durable. The depiction of a giant sea serpent published by the Dutch zoologist Anthonie Oudemans in 1892, is not unlike many depicted in mosaics from Antiquity or in books from the Middle Ages and Early Modern period. Towards the end of the nineteenth century sightings of this mythical creature were still reported with such regularity that Oudemans was able to collect nearly two hundred reports over the course of three years. Applying what is known as a crypto-zoological approach, in the absence of empirical evidence, Oudemans used the quantity of sightings as an argument that the giant sea serpent was an existing species. He proposed the scientific name Megophias megophias for the yet to be discovered creature. Oudemans received a lukewarm reaction from the academic world, where both cryptozoology and the existence of sea-monsters were considered controversial. Nonetheless, The Great Sea Serpent was published by reputable academic publishers. As Oudemans pointed out, the fact that a sea-monster has not yet been discovered does not prove it does not exist.

The sea-monster, as Mr. C. Renard supposed to have seen it, in Anthonie Cornelis Oudemans, The great sea-serpent: An historical and critical treatise: With the reports of 187 appearances, Leiden, Brill etc. – London, Luzac & Co, 1892, p. 56. [Leiden University Library, 290 B 7]