Home » Posts tagged 'Conrad Gessner'

Tag Archives: Conrad Gessner

Fantastic Beast and How to Make Them. Part I

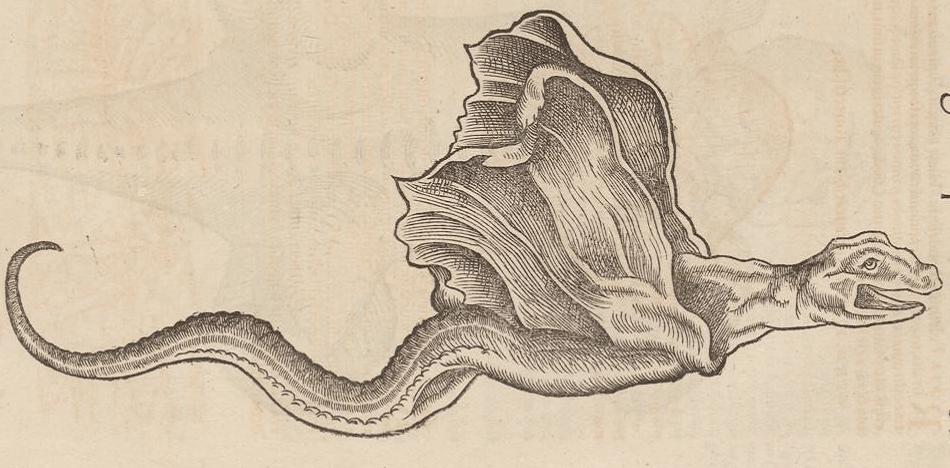

A year and a half ago in a blogpost on sixteenth century Monstreous Rays and Fraudulent Apothecaries, I referred to a description of a sea-creature resembling a winged snake or a dragon from Conrad Gessner’s 1558 Historia Piscium. Last weekend my colleague Robbert Striekwold and I made an attempt at making such a dragon ourselves. Our project at Leiden University, A New History of Fishes, is at the moment organising an exhibition at the Leiden University Library which opens on September 20. If by then we have managed to create a dragon that looks like Gessner’s, this will be put on display. The photo below shows our first, somewhat clumsy, attempt. We used the wrong type of fish, and the result is a far cry from Gessner’s dragon. However, we will continue to try, and so this blogpost is the first of a series.

Gessner described how sea-monsters were made out of rays, often by apothecaries who displayed them in their shops. For more information on these monstrosities, nowadays known as Jenny Hanivers, I refer to my previous blogpost. For now, let’s return to Gessner’s text for a moment.

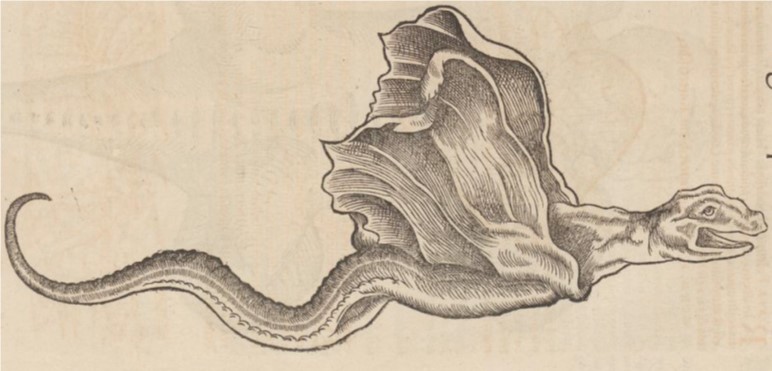

“Apothecaries and others”, he writes, “let the body of the ray dry and twist the skeleton, making the animal look like a winged serpent or a dragon. They bend the body and alter the shape of the head and mouth, and cut other parts off. The forward part of the wings is cut away, and what is left is turned upright, making the animal look like it has wings”

Conrad Gesner. Historiae animalium liber IIII. Zurich, Christoph Froschauer, 1558. SUB Göttingen HSD

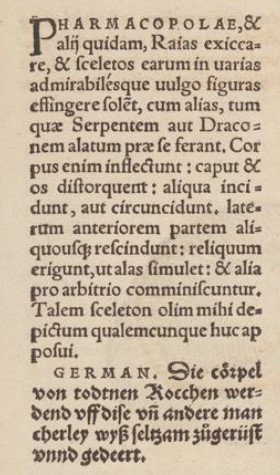

Gessner complained that ordinary people were easily impressed by such things, referring to the fact that such man-made monsters were often exhibited and people would readily pay to see them. Jenny Hanivers were therefore no rare sight. Gessner’s acquaintance, the naturalist Ulysse Aldrovandi (1522-1605) depicted no fewer than five of them.

Ulysse Aldrovandi. De piscibus. Bologna, Baptiste Bellagamba, 1613. Université Louis Pasteur from University of Strasbourg.

To us this suggested that they might not be so difficult to make, and armed with Gessner’s instructions we set out to try this for ourselves. However, we faced several challenges, beginning at the fish market. Rays, I had been told, are at their leanest and therefore not sold during the summer. However, with a few days notice, my fishmonger could get me one. Unfortunately, when I came to collect my ray, it had been chopped up and neatly wrapped up with a lemon and a bunch of parsley. Unable to get another ray at short notice, Robbert and I decided to practice on the scariest looking thing we could find, a monkfish (Lophius piscatorius).

Photo: Kai Henry

Of course monkfish are nothing like rays, and, because they are much more fleshy, much less suitable for our purpose. Nevertheless, we got to work. We knew certain parts of the fish would be impossible to preserve, so our first step was to remove those, beginning with the eyes.

Then we turned our fish over and began to remove as much flesh as possible, leaving the bone and the skin. This would make it easier to twist and shape, and would hopefully leave us with something that would easily dry in the sun. Having chosen a hot day for our experiment, we were hopeful. Monkfish have a thick spinal cord and no small bones, and so, using a standard dissection kit, we were able to easily remove almost all of the flesh from the tail. The head however, contains a lot of cartilage and we couldn’t get to the fleshy parts.

Not wanting to let this discourage us, we began to shape our fish. Because Gessner’s instructions applied to rays, we abandoned them and used our imagination. We decided to spread out the pectoral fins and lift them to make them look like wings, twist the tail and spread out the dorsal fin, and open the mouth wide for a scary finishing touch. Then of course everything had to be kept in position until it dried. We began with the tail, and pinned the tail fin down. All the while, we kept spraying water on our fish to keep it from drying out before we’d shaped it.

The next step was to spread out and lift the dorsal fin. This was easy enough, but then we had to keep it like this until it was dry. Some wooden building blocks my son no longer plays with came in useful. We propped one up against the fin and used a pipe cleaner to provide extra support.

Then we spread out and lifted the pectoral fins, using the same system. We propped them up using blocks, then used aluminium wire for extra support. This accomplished, we added pipe cleaners to hold up the filaments on the head. By now our fish was beginning to somewhat resemble Frankenstein’s monster.

We moved on to the head, again using building blocks and wire. We wrapped the wire around the head and stuffed one of the blocks into the mouth. And just like that we were done, now all we had to do was leave our creation out in the sun and hope for it to dry.

And here comes the sad part. After a long and well deserved lemonade break during which we named our monster Oscar, we returned to find the fins fairly dry but everything else more or less like we left it. By now it was late afternoon, Robbert had to go home and we left Oscar on my roof terrace, hoping he would magically dry while my family and I had dinner.

That evening, once the kids were in bed, my husband and I went to check on Oscar. He had begun to dry out but still had a long way to go, and the sun was going down. Not wanting to give up, and not wanting to leave Oscar unprotected in case the neighbourhood cats would feast on him, we put him on salt and in a box.

The next morning I went to check on him. The salt had little to no effect, Oscar was still wet. And so, once again I left him out in the sun and hoped for the best.

It was not to be. By evening, Oscar had begun to decompose and smell. He was also attracting flies.

It was time to make a decision. And so Oscar went into the bin…

Nevertheless, Oscar taught us a few valuable lessons. Making a dragon like Gessner’s is fairly easy, however drying it proves difficult. In this case, we did not manage to remove quite enough flesh, but this may be easier working with rays, as Gessner prescribes. And while we hoped that leaving Oscar out in the sun and putting him on salt would do the trick, we should keep in mind that Gessner does not explain how to dry the fish, therefore we may have to consider other methods.

This weekend we will try again. This time using a ray and following Gessner’s instructions to the letter. To be continued..

Further reading:

Pierre Belon. De aquatilibus. Paris, Charles Estienne, 1553.

Conrad Gesner. Historiae animalium liber IIII. Zurich, Christoph Froschauer, 1558.

Ulysse Aldrovandi. De piscibus. Bologna, Baptiste Bellagamba, 1613.

Sophia Hendrikx. Het eerste en misschien ook wel het kleinste en mooiste boek over waterdieren. In: Hans Mulder en Erik Zevenhuizen (Red.), De natuur op papier. 175 jaar Artis Bibliotheek. Amsterdam, Athenaeum-Polak & Van Gennep, 2013.

Peter Dance. Animal frauds and fakes. Maidenhead, Berkshire, Sampson Low, 1976.

© Sophia Hendrikx and Fishtories, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Sophia Hendrikx and Fishtories with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Spontaneously Generating Fish

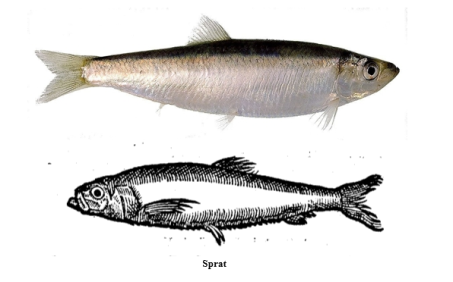

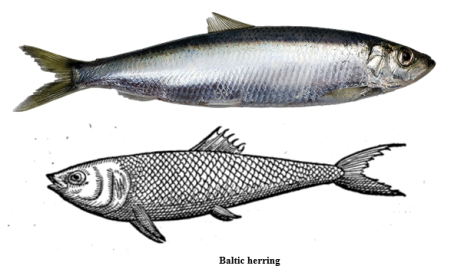

In a previous blogpost I discussed how the Swiss scholar Conrad Gessner (1516-1565) describes two strange species of fish, which generate spontaneously. Previously I identified these species as the sprat and the Baltic herring. In this blogpost I explore the background of Gessner’s assumptions about the spontaneous generation of fish.

The Reproduction of Fish

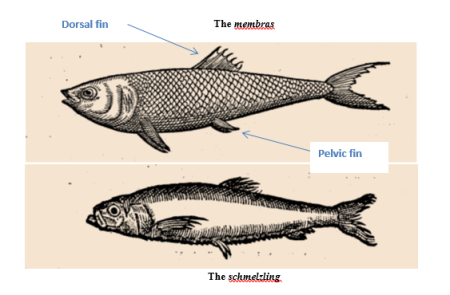

In his 1558 book on fish Historia Piscium Conrad Gessner describes the membras, which I identified as the Baltic herring in my last blog post:

‘Aristotle writes that the membras comes from the aphya phalerica.’

This is confirmed in his description of the aphya phalerica, which was identified as the sprat:

‘The aphya phalerica is mentioned by Aristotle, and it is confirmed the membras comes from this. I believe that the aphya phalerica generates spontaneously’

This tells us that the author believes these fishes to generate spontaneously, which seems somewhat surprising. The study of fish was a booming topic in Gessner’s day, from around 1550 renowned scholars produced one publication on fish after the other. All of these experts agreed that fish reproduce sexually. In fact, Gessner described this reproduction process in detail. He makes an exception however, for these two as well as a handful of other species. Why does he do this?

Fig. 1 Gessner’s sprat, or aphya phalerica. Historia Piscium. Zurich, Froschauer, 1558.

Spontaneous Generation

A belief in spontaneous generation, the coming into existence of living beings not from parents but through some other means, originates in the classical era and was still widely accepted within the scholarly community in the sixteenth century. Small creatures, such as for example insects, were thought to generate spontaneously. Some base material was needed for this, often dirt, mud, or decaying matter. From this material a living creature would form spontaneously. As Gessner indicates in his descriptions, we can trace such ideas back to Aristotle’s History of Animals. Aristotle combined information obtained from a variety of sources, resulting in an overview of ideas commonly accepted in the classical era. One such idea was spontaneous generation. While, like Gessner, Aristotle acknowledges that most fish reproduce sexually, he believed that some were the result of spontaneous generation.

Discussing fish, in book VI, part 15, of his History of Animals, Aristotle states:

“Such fish as are neither oviparous nor viviparous arise all from one of two sources, from mud, or from sand and from decayed matter that rises thence as scum”

Fig. 2 Spontaneous generation. Clipart Library

Empirical Evidence?

Aristotle’s ideas were absorbed into Mediaeval, and later into Renaissance science. The idea that animals sometimes generated spontaneously remained more or less unchallenged, and often even seemed to be confirmed by experience. For example, a century after Gessner published his work, the Dutch artist Johannes Goedaert (1617-1668) left out a cup of his own urine and watched it over a period of time. Eventually flies emerged from the cup and, not having noticed the fly that must have laid its eggs near this rich source of nutrients, he took this to prove spontaneous generation. Goedaert would later change his mind but for a while found this experiment quite convincing. Similarly, a little before Goedaert conducted his experiment, Jan Baptist van Helmont (1580-1644) felt confident to provide the following recipe for mice: Place a dirty shirt or some rags in an open pot or barrel containing a few grains of wheat or some wheat bran, and in 21 days, mice will appear.

Fig. 3 Where there is grain, there are mice. A Video (17/ 6/ 2016), Little mouse in barrel with wheat. Retrieved from youtube.com.

This illustrates perfectly why the concept of spontaneous generation proved so durable, our own observations often seem to confirm it. We can conclude from Aristotle’s History of Animals that the same sort of confusing experience appeared to confirm the concept in antiquity. Aristotle backs up his claim that certain fish can generate spontaneously by citing observations that others have shared with him.

“As a proof that these fish occasionally come out of the ground we have the fact that in cold weather they are not caught, and that they are caught in warm weather, obviously coming up out of the ground to catch the heat; also when the fishermen use dredges and the ground is craped up fairly often, the fishes appear in larger numbers.”

Fig. 3. Fishing in the mud. Tim Bunn (22/5/2008), Mud Fishing in India. Retrieved from youtube.com.

A Chain of Fishes

Aristotle imagined the spontaneous generation of such fish as a sort of chain. According to him, while very small fishes generate from foam that floats on the sea, larger fishes generate from the remains of the deceased smaller fish. A list is provided.

“From the aphya phalerica comes the membras, from the membras the trichis,[and] from the trichis the trichias.”

When the aphya phalerica dies, the membras generates from its decaying matter, when the membras dies the trichis generates from its remains, followed in due course by the trichias. As we can see, Gessner’s membras and aphya phalerica are mentioned here. This also explains why Gessner describes the former as springing from the latter. The aphya phalerica is the first stage in this chain of spontaneously generating fishes.

Fig. 4 A chain of fishes. Source: Clipartkid

In the Footsteps of Aristotle

In Gessner’s day, Aristotle, as the founding father of natural history, was considered a much esteemed source of information. For this reason, Gessner and his contemporaries heavily relied on the information provided by him. Is this then a full explanation why Gessner believes these two fishes to generate spontaneously? It seems that Gessner was familiar with current catch records and market prices of the sprat, suggesting he had an informant who may have observed these species first hand. Surely someone like this, well-informed and possibly in possession of first-hand information, would know that the sprat springs from sexual generation as all other fishes do?

According to Aristotle this does not matter. He writes:

“the great majority of fish then, as has been stated, proceed from eggs. However, there are some fish that proceed from mud and sand, even of those kinds that proceed also from the pairing and the egg.”

Consequently, just because you have observed that a species sometimes comes from sexual generation, this does not mean they cannot also come from spontaneous generation. It really is quite hard to argue with that.

To Be Continued…

Is this all that is to be said on the aphya phalerica and the membras? Not quite. Closer inspection reveals that Gessner and Aristotle are not describing the same species. Where to Gessner an aphya phalerica is a sprat and a membras is a Baltic herring, to Aristotle the aphya phalerica was the anchovies and the membras something undefined, a large anchovies or another small fish. In a future blogpost we will explore this linguistic confusion.

Fig. 5 Sprats in tomato sauce. Source: Irina Slutsky

Further reading:

Aristotle, History of Animals.

Conrad Gessner, Historia Piscium. Zürich, Froschauer, 1558.

Sophia Hendrikx, Identification of herring species in Conrad Gessner’s ichthyological works, a case study on taxonomy, nomenclature, and animal depiction in the sixteenth century. In: Paul J. Smith and Karl A.E. Enenkel (Eds.), Zoology in Early Modern Culture. Intersections of Science, Theology, Philology and Political and Religious Education. Leiden, Brill, 2014.

This post also appeared on the Leiden Arts in Society Blog.

© Sophia Hendrikx and Fishtories, 2017. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Sophia Hendrikx and Fishtories with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Monstrous rays and fraudulent apothecaries

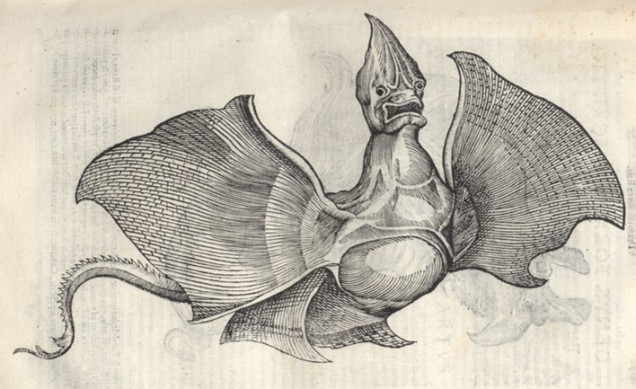

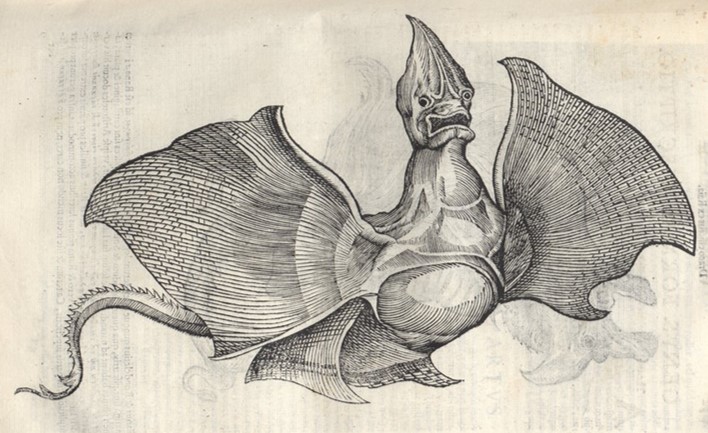

In 1553 the French naturalist Pierre Belon published, in his book on aquatic animals De Aquatilibus, the here shown depiction of what at first glance appears to be a frightening sea-monster. Belon’s discussion of this animal is serious and detailed. This animal catches it’s prey by leaping up from the water, he writes, and he advises his readers not to eat it. It has a foul taste and smell, he explains, and can upset the stomach.

Pierre Belon. De aquatilibus. Paris, Charles Estienne, 1553. Library of the United States Department of Agriculture, Cambridge (Mass.).

What Belon fails to mention, and most likely did not know, is that this animal is in fact a European eagle ray which has been cut and twisted before being dried, in order to make it look like a monster. The distorted snout and twisted body are sure sights of human interference, and in fact such distorted rays were created on a large scale across Europe at this time. In the sixteenth century monsters were very much ‘in fashion’, and this widespread interest made it a lucrative business to create objects that could reasonably pass as monstrous creatures.

The European eagle ray. Image by Patrik Neckman from Stockholm, Sweden (Majestic ray) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Five years later, in 1558, the less gullible Conrad Gessner included such a creation in his Historiae Animalium and explained to his readers exactly how these were made. “Apothecaries and others”, he writes, “let the body of the ray dry and twist the skeleton, making the animal look like a winged serpent or a dragon. They bend the body and alter the shape of the head and mouth, and cut other parts off. The back and bottom part of the animal is tampered with and turned upright, making the animal look like it has wings”

Conrad Gesner. Historiae animalium liber IIII. Zurich, Christoph Froschauer, 1558. SUB Göttingen HSD

Gessner admits that he also initially did not know the animal was a fake. The depiction was sent to him by an apothecary, who did not disclose this. Eventually however, he figured it out, and he strongly disapproved of the practice. He explains that he discloses how these creatures are made in order to warn his readers about these fakes, and about the fraudulent people who exhibit them and charge others money to see them. This needs to be explained, he writes, as “ordinary people are very much impressed with these things”.

Part of Gessner’s description of the dried ray. SUB Göttingen HSD

Rays and skates are in fact extremely suitable to make creations such as these. These fish already have a suggestive appearance, their underside looks to us as if we see a semi-human face, the nostrils looking like a pair of eyes. In addition, they can be easily manipulated, by curling the side fins over the back, twisting the tail into strange positions, and using string tied behind the head to create a neck. Finally, rays and skates can be easily dried in the sun, and shrink when this is done, resulting in an even more twisted and monstrous appearance.

Image by Adamantiaf. (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1613 Gessner’s acquaintance and correspondent Ulysse Aldrovandi published a range of depictions of such monstrous dried rays, or jenny hanivers as they are nowadays called, in his De piscibus. The origin of the term jenny haniver may lie in the French phrase jeune d’Anvers, Antwerp having been a centre of production for these things.

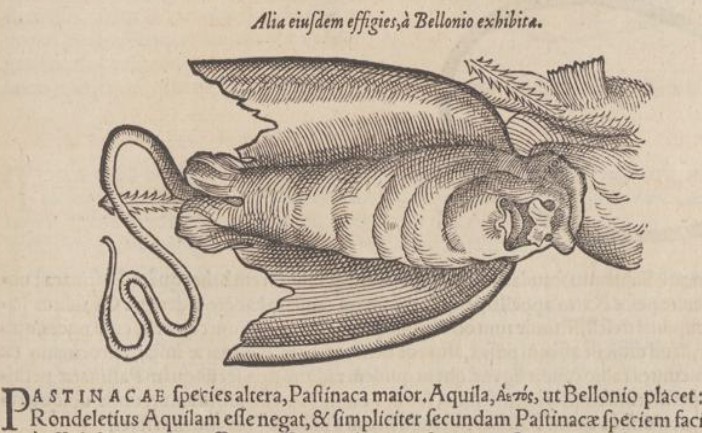

An ardent collector of all sorts of naturalia Aldrovandi may well have seen and handled all the jenny hanivers he included in his book. It is known he owned several of them. The here shown depictions shows one which resembles a flying dragon which looks like it is mid-flight. Much like Gessner, Aldrovandi clearly indicates that such creatures are not real.

Ulysse Aldrovandi. De piscibus. Bologna, Baptiste Bellagamba, 1613. Université Louis Pasteur from University of Strasbourg.

So does this mean that once the word was out naturalists were more sceptical about reports they received about strange creatures from the sea? Perhaps that is an overstatement. In spite of his critical description of the above shown specimen, Gessner also shows Belon’s jenny haniver in his Historiae Animalium and copies Belon’s description of it almost word for word, without any of the criticism voiced in his description of the other jenny haniver. One possible explanation for this is that it mattered to Gessner whether or not information came from what he perceived as a reliable source. An esteemed naturalist such as Pierre Belon was certainly that.

Conrad Gesner. Historiae animalium liber IIII. Zurich, Christoph Froschauer, 1558. SUB Göttingen HSD

On top of this, just because something seems unlikely does not necessarily mean it isn’t true. As Gessner writes referring to other monstrous creatures, such as the sea-monk and the sea-satyr: some creatures have been reported either so often or by such reliable sources that he cannot exclude the possibility that they exist.

Further reading:

Pierre Belon. De aquatilibus. Paris, Charles Estienne, 1553.

Conrad Gesner. Historiae animalium liber IIII. Zurich, Christoph Froschauer, 1558.

Ulysse Aldrovandi. De piscibus. Bologna, Baptiste Bellagamba, 1613.

Sophia Hendrikx. Het eerste en misschien ook wel het kleinste en mooiste boek over waterdieren. In: Hans Mulder en Erik Zevenhuizen (Red.), De natuur op papier. 175 jaar Artis Bibliotheek. Amsterdam, Athenaeum-Polak & Van Gennep, 2013.

Peter Dance. Animal frauds and fakes. Maidenhead, Berkshire, Sampson Low, 1976.

© Sophia Hendrikx and Fishtories, 2016. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Sophia Hendrikx and Fishtories with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

This blogpost also appeared on The Leiden Arts and Society Blog.

Eat What You Are: 16th century medical advice

The poem rea ds:

ds:

All sorts of fish, big and small, young and old,

Are all moist and in addition also cold,

River trout and bullheads are best to eat,

In January when the farmers thresh their wheat.

Image: Bayerische StaatsBibliothek

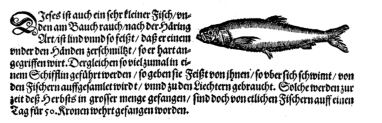

This is a page from a 1557 book on fishes from Lake Constance by fish fanatic Gregor Mangolt. A former priest turned protestant, Mangolt had to flee his native Germany and ended up in Switzerland, where he met and befriended the scholar Conrad Gessner, who like Mangolt happened to be fascinated with fish. This turned out to be fruitful encounter.

A few years earlier Gessner had published a calendar together with the local physician and all round celebrated literary, political and medical writer Jakob Ruf. Gessner supplied the images while Ruf supplied the text. Each month of the year was illustrated with a depiction of two local fishes and a short poem. The poems dispense advice on eating fish, reasoning from a medical perspective.

At the time the dominant medical theory was humouralism. This states that people’s personalities and their physical condition depend on the presence of four different fluids in their body: yellow bile, black bile, blood, and phlegm. If one of these is present in excess, body and mind are out of balance. The balance can be restored (or disturbed even more!) by the consumption of certain foods.

Since fish live in water they are, as the poem states, cold and wet. These are qualities that increase the amount of phlegm in the body. The eating of fish was consequently tricky business.

An excess of phlegm made a person phlegmatic, a condition that was best avoided. On the other hand, if a person had an excess of certain other fluids but a lack of phlegm, eating fish could restore balance. It could change aggressive personalities and people who tended to drink and eat to excess into more moderate people. In order to decide what you should eat, you should therefore first consider who you were. In order to make sure the right people ate fish, and others did not, the calendar provides playful instructions through the included poems.

When Gessner read Mangolt’s book of fish, which provides descriptions of a range of local species, he felt this would go well with his fish calendar. Mangolt did not provide illustrations and his text is rather dry, the addition of Gessner’s calendar certainly made it more lively. On the other hand, Gessner’s calendar provided little serious information and Mangolt’s text could provide a welcome balance.

There was only one problem, Mangolt did not want his fish book published.

This however did not deter Gessner. He asked to borrow the manuscript and took it to his cousin, Andreas Gessner, who was a printer. The Gessner cousins then proceeded to mix the calendar and Mangolt’s text to create a joint publication. The above image is one of the first pages of the end result. When the book was printed the Gessners listed Mangolt as the sole author on the title page.

We can only guess how Mangolt felt about this. However we do know that the book was reprinted at least twice, it appears therefore that he put his reservations about publishing his work aside.

That being said, the calendar was removed from the later two editions…

Further reading:

- Keller, Hildegard Elisabeth: Edition, Einleitung und Kommentar der Fischsprüche. In: Keller, Hildegard Elisabeth (Hg.): Jakob Ruf. Leben, Werk und Studien, Zürich 2008 (Jakob Ruf, Leben, Werk Studien Vierter Band), S. 967-993.

Also see: Conrad Gessner Historiae Piscium – Rare Fish Books

Sophia Hendrikx and Fishtories, 2016. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to the author and Fishtories with appropriate and specific direction to the original content

Sprat?

Sprat?