Home » 2017

Yearly Archives: 2017

Lactating creatures with double genitals and the head of a cow. Describing New World ‘whales’ in the sixteenth century.

In his 1554 book on fishes and other aquatic creatures the, at that time, widely renowned French naturalist Guillaume Rondelet described three mysterious species he classified as ‘whales’ from the new world. Although he had very little information on these animals, he was able to report several intriguing and exciting facts about them. All three of them appeared to be mammals, as they gave birth to live young and fed these with milk. One could be trained like a dog. And to top it all off, two have not one, but two full sets of genitals. Which animals were these? Where did Rondelet obtain his information? And what on earth is going on with those double sets of genitals?

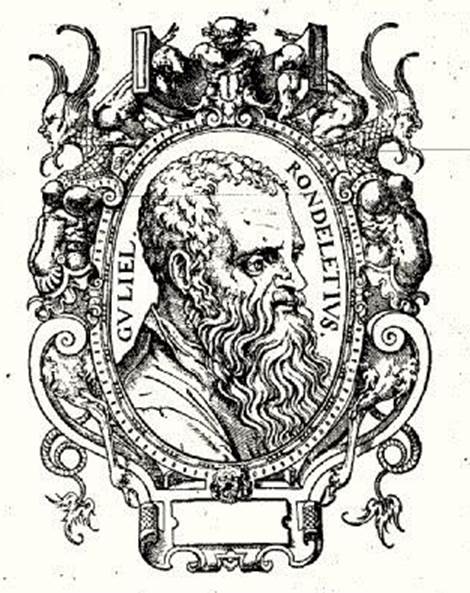

Woodcut portrait of Guillaume Rondelet, from his work Libri de Piscibus Marinis (1554). Bibliothèque National de France: Gallica.

Out of character

It was unusual for Rondelet to describe animals he knew very little about. As professor of comparative anatomy at the university of Montpellier, he was convinced that the body parts of animals had been created as perfectly adapted for their specific environment. Consequently, he felt they should be studied in this environment, and he often joined fisherman’s crews to do just that. Following such trips, he took specimens home, kept them in tanks, studied them and experimented on them. Usually, this did not end well for the fish. For example, Rondelet successfully proved, by sealing a tank, that even fish need a supply of fresh air to survive.

Although the fish that helped him prove this gave its life for science, in the end it didn’t matter much, as Rondelet had a habit of eventually dissecting the fish he studied. In short, he considered personal observation part of the foundation of his study of nature, and included in his book only a handful of species he had never seen. An exception was made however, for these species, which he could not successfully identify and of which no depiction could be obtained. Rondelet provides no further information that that these are species from “the Indies”, by which he means the America’s, without further narrowing down the region, and does not indicate who his source of information was. It is likely he was intrigued by the spectacular descriptions.

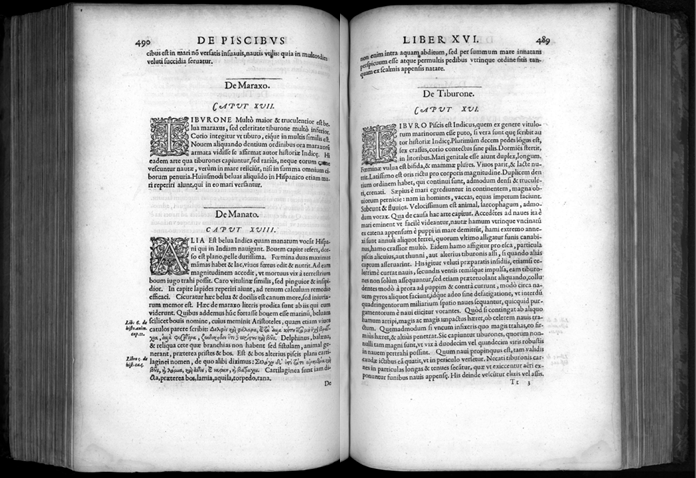

Rondelet’s description of New World ‘whales’ in his Libri de Piscibus Marinis (1554). Bibliothèque National de France: Gallica.

Identifications

He called these three mysterious species, the manatus, tiburus, and maraxus. Only the first is easy to identify. The female manatus, the description reads “has two teats, and produces milk to feed her offspring”. In addition, she is “docile as a dog”, as reported “by those who have seen it”. All and all, we can quite easily conclude that this is a manatee, or sea cow. These species are cetaceans and mammals and do not often display aggressive behaviour. Most likely this is a West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus).

West Indian Manatee. Keith Ramos.

This leaves us with the two species that are described as having two sets of genitals. The description states that the tiburus “has a uterus which is divided into two chambers, and several teats” and “gives birth to live young, and feeds them with milk”. The name tiburus may be based on the Spanish tiburón, meaning shark. The remark that the uterus has two chambers could refer to the fact that many shark species are ovo-viviparous. While they produce eggs, these hatch internally, and the offspring are transferred to another part of the reproductive system. This could then be any live-bearing shark species. Since sharks are not mammals, they don’t feed their young with milk, but since they are live-bearing, this assumption is easily made.

Possibly, this is a great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier), or the shortfin mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus). The fact that the males are described as having double genitalia, “genitale esse aiunt duplex”, may well refer to a shark’s claspers, an extension of the male pelvic fins used in mating. A shark has two claspers, simply because it also has two pelvic fins.

Short fin mako shark. Jidanchaomian.

Sources and etymology

That the names would come from Spanish is not altogether surprising. Since the late fifteenth century, Spanish explorers of the new world had encountered aquatic species in the Caribbean. In turn, the name maraxus appears to be based on the Spanish marrajos, a term which can apply to several shark species, but predominantly refers to the shortfin mako shark. However, the marrajos is described in Bartolomé de Las Casas’ Apologetica Historia Sumaria (1527-), where it is said to inhabit shallow waters near the coast. This could indicate that rather than the mako, this could be the great white shark.

Since de Las Casas did not appear in print until 1958, Rondelet would not have been familiar with this text. The earliest work describing aquatic species from the new world, appears to be Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo’s Sumario de la Natural Historia de las Indias (1526). This discusses turtles, sharks, and the manatee. While he does not indicate this, most likely, this was Rondelet’s source of information.

Great white shark. George Probst.

This still leaves us with one question. Rondelet would have been unfamiliar with the Spanish words tiburón and marrajos. Since the species Spanish explorers encountered in the New World were very different from these they were familiar with, and they consequently lacked words to describe them, they tended to turn to local knowledge and used bastardised Indian names to describe them. According to the lexicographer Fernando Ortiz, tibur´on comes from the Carib language. Possibly ti means ground and bur´on means fish. Similarly towards the end of the sixteenth century, English explorers would adopt the word xoc from the Mayans, which is the root of the word shark.

Scepticism

This being as it may, the double genitals of the tiburus and maraxus should have made Rondelet realise that these were shark species. European shark species, although very different in size to American shark species, also have claspers. In addition, it had been known since antiquity that sharks were live-bearing fishes rather than mammals, as they described as such in Aristotle’s History of Animals. The fact that Rondelet describes these species as producing milk indicates he had not realised they were sharks, but how is this possible? The way in which the description is phrased, “genitale esse aiunt duplex”- they say it has double genitals, could indicate that the author was not convinced this was true. The verb aiunt, meaning ‘they say’, could imply a certain scepticism, which is understandable in relation to this description of a completely unknown animal. Most likely then, Rondelet felt these descriptions were too spectacular to be completely true, and therefore decided not to draw conclusions.

Further reading:

Guillaume Rondelet, Libri de piscibus marinis. Mathieu Bonhomme, Paris, 1554, p. 1-112 (introduction) & 489-490 (manatus, tiburus & maraxus).

Bartolomé de Las Casas, Apologetica historia sumaria. Bibliotheca de Autores Españoles 105. Obras Escogidas de Bartolome de las Casas III. Ediciones Atlas, Madrid, 1958.

Ortiz, Fernando. Nuevo catauro de cubanismos. Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, Havana, 1974.

This post also appeared on the Arts in Society Blog.

© Sophia Hendrikx and Fishtories, 2017. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Sophia Hendrikx and Fishtories with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Spontaneously Generating Fish

In a previous blogpost I discussed how the Swiss scholar Conrad Gessner (1516-1565) describes two strange species of fish, which generate spontaneously. Previously I identified these species as the sprat and the Baltic herring. In this blogpost I explore the background of Gessner’s assumptions about the spontaneous generation of fish.

The Reproduction of Fish

In his 1558 book on fish Historia Piscium Conrad Gessner describes the membras, which I identified as the Baltic herring in my last blog post:

‘Aristotle writes that the membras comes from the aphya phalerica.’

This is confirmed in his description of the aphya phalerica, which was identified as the sprat:

‘The aphya phalerica is mentioned by Aristotle, and it is confirmed the membras comes from this. I believe that the aphya phalerica generates spontaneously’

This tells us that the author believes these fishes to generate spontaneously, which seems somewhat surprising. The study of fish was a booming topic in Gessner’s day, from around 1550 renowned scholars produced one publication on fish after the other. All of these experts agreed that fish reproduce sexually. In fact, Gessner described this reproduction process in detail. He makes an exception however, for these two as well as a handful of other species. Why does he do this?

Fig. 1 Gessner’s sprat, or aphya phalerica. Historia Piscium. Zurich, Froschauer, 1558.

Spontaneous Generation

A belief in spontaneous generation, the coming into existence of living beings not from parents but through some other means, originates in the classical era and was still widely accepted within the scholarly community in the sixteenth century. Small creatures, such as for example insects, were thought to generate spontaneously. Some base material was needed for this, often dirt, mud, or decaying matter. From this material a living creature would form spontaneously. As Gessner indicates in his descriptions, we can trace such ideas back to Aristotle’s History of Animals. Aristotle combined information obtained from a variety of sources, resulting in an overview of ideas commonly accepted in the classical era. One such idea was spontaneous generation. While, like Gessner, Aristotle acknowledges that most fish reproduce sexually, he believed that some were the result of spontaneous generation.

Discussing fish, in book VI, part 15, of his History of Animals, Aristotle states:

“Such fish as are neither oviparous nor viviparous arise all from one of two sources, from mud, or from sand and from decayed matter that rises thence as scum”

Fig. 2 Spontaneous generation. Clipart Library

Empirical Evidence?

Aristotle’s ideas were absorbed into Mediaeval, and later into Renaissance science. The idea that animals sometimes generated spontaneously remained more or less unchallenged, and often even seemed to be confirmed by experience. For example, a century after Gessner published his work, the Dutch artist Johannes Goedaert (1617-1668) left out a cup of his own urine and watched it over a period of time. Eventually flies emerged from the cup and, not having noticed the fly that must have laid its eggs near this rich source of nutrients, he took this to prove spontaneous generation. Goedaert would later change his mind but for a while found this experiment quite convincing. Similarly, a little before Goedaert conducted his experiment, Jan Baptist van Helmont (1580-1644) felt confident to provide the following recipe for mice: Place a dirty shirt or some rags in an open pot or barrel containing a few grains of wheat or some wheat bran, and in 21 days, mice will appear.

Fig. 3 Where there is grain, there are mice. A Video (17/ 6/ 2016), Little mouse in barrel with wheat. Retrieved from youtube.com.

This illustrates perfectly why the concept of spontaneous generation proved so durable, our own observations often seem to confirm it. We can conclude from Aristotle’s History of Animals that the same sort of confusing experience appeared to confirm the concept in antiquity. Aristotle backs up his claim that certain fish can generate spontaneously by citing observations that others have shared with him.

“As a proof that these fish occasionally come out of the ground we have the fact that in cold weather they are not caught, and that they are caught in warm weather, obviously coming up out of the ground to catch the heat; also when the fishermen use dredges and the ground is craped up fairly often, the fishes appear in larger numbers.”

Fig. 3. Fishing in the mud. Tim Bunn (22/5/2008), Mud Fishing in India. Retrieved from youtube.com.

A Chain of Fishes

Aristotle imagined the spontaneous generation of such fish as a sort of chain. According to him, while very small fishes generate from foam that floats on the sea, larger fishes generate from the remains of the deceased smaller fish. A list is provided.

“From the aphya phalerica comes the membras, from the membras the trichis,[and] from the trichis the trichias.”

When the aphya phalerica dies, the membras generates from its decaying matter, when the membras dies the trichis generates from its remains, followed in due course by the trichias. As we can see, Gessner’s membras and aphya phalerica are mentioned here. This also explains why Gessner describes the former as springing from the latter. The aphya phalerica is the first stage in this chain of spontaneously generating fishes.

Fig. 4 A chain of fishes. Source: Clipartkid

In the Footsteps of Aristotle

In Gessner’s day, Aristotle, as the founding father of natural history, was considered a much esteemed source of information. For this reason, Gessner and his contemporaries heavily relied on the information provided by him. Is this then a full explanation why Gessner believes these two fishes to generate spontaneously? It seems that Gessner was familiar with current catch records and market prices of the sprat, suggesting he had an informant who may have observed these species first hand. Surely someone like this, well-informed and possibly in possession of first-hand information, would know that the sprat springs from sexual generation as all other fishes do?

According to Aristotle this does not matter. He writes:

“the great majority of fish then, as has been stated, proceed from eggs. However, there are some fish that proceed from mud and sand, even of those kinds that proceed also from the pairing and the egg.”

Consequently, just because you have observed that a species sometimes comes from sexual generation, this does not mean they cannot also come from spontaneous generation. It really is quite hard to argue with that.

To Be Continued…

Is this all that is to be said on the aphya phalerica and the membras? Not quite. Closer inspection reveals that Gessner and Aristotle are not describing the same species. Where to Gessner an aphya phalerica is a sprat and a membras is a Baltic herring, to Aristotle the aphya phalerica was the anchovies and the membras something undefined, a large anchovies or another small fish. In a future blogpost we will explore this linguistic confusion.

Fig. 5 Sprats in tomato sauce. Source: Irina Slutsky

Further reading:

Aristotle, History of Animals.

Conrad Gessner, Historia Piscium. Zürich, Froschauer, 1558.

Sophia Hendrikx, Identification of herring species in Conrad Gessner’s ichthyological works, a case study on taxonomy, nomenclature, and animal depiction in the sixteenth century. In: Paul J. Smith and Karl A.E. Enenkel (Eds.), Zoology in Early Modern Culture. Intersections of Science, Theology, Philology and Political and Religious Education. Leiden, Brill, 2014.

This post also appeared on the Leiden Arts in Society Blog.

© Sophia Hendrikx and Fishtories, 2017. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Sophia Hendrikx and Fishtories with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.